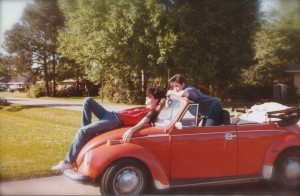

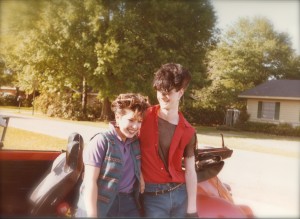

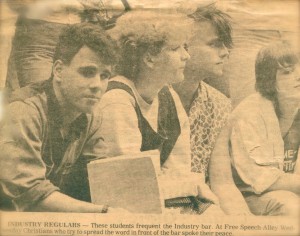

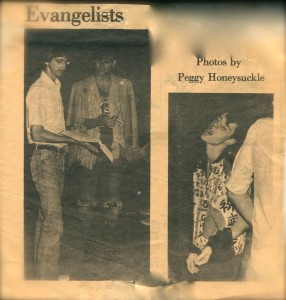

Not-so-random pictures and news clippings from Baton Rouge’s Chimes Street ‘Ghetto,’ the Bayou, Industry Bar, and Louisiana State University’s free speech alley, ca.1982-1983.

I’m inspired to collect these here because punk-ish history often verges on cliché, or risks being reduced to nostalgia for your 1980s playlist, and I wanted to personalize the larger story, bring it down to earth a bit. Here goes.

These two decidedly unsurly kids in a decidedly suburban setting were far away from the Chimes Street Ghetto where the young man (TW) lived in those days.

The broken Cramps album is mine; the other half was TW’s, but I don’t know if he kept his. I wasn’t a flame for him the way he was for me, so I imagine it became smithereens after some Chimes Street party or other.

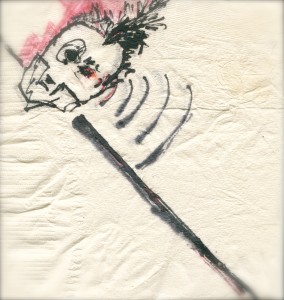

This well-preserved napkin study lived in a stack of old polaroids for years. It was a quick sketch of a small graffito I drew with markers on a Ghetto wall near TW’s apartment. Never got a picture of it before it was painted over. No camera in those lean days, and no camera phones.

Clips from The Daily Reveille (LSU’s school paper) are from free speech alley and the nearby Industry Bar, a venue for music and art shows. Baton Rouge had lots of post-hippie, pre-hip energy, but it also seemed overrun by rude puritans in those days. I remember them like they were walking Ralph Steadman cartoons, full of fear and loathing.

At the Industry Bar, pushy religious zealots often crowded the entrance as a protest if they didn’t like the act or the art show du jour. Often, harsh words were exchanged, shoving broke out. Cops kept a watchful eye, but no arrests of either side were made, as far as I know. Kids went on to art and music, as we will, but I never forgot these run-ins.

At the Industry Bar, pushy religious zealots often crowded the entrance as a protest if they didn’t like the act or the art show du jour. Often, harsh words were exchanged, shoving broke out. Cops kept a watchful eye, but no arrests of either side were made, as far as I know. Kids went on to art and music, as we will, but I never forgot these run-ins.

Years later, in graduate school all the way across the country, I again ran into two of the most infamous instigators of the campus ministry movement, Brother Jed and Sister Cindy. They hadn’t changed one bit. At LSU, they were just two of many evangelists in the early 1980s who used campus free speech zones to spew brimstone, and they were particularly vitriolic towards the punks—the feeling was mutual, believe me. Fun fact! These holy rollers hated other Christian sects (like Catholics, who were a big constituency at LSU) as much as they hated homosexuals or punks. Serious disputes were common between them and those of us who didn’t give a shit about someone’s sexuality/identity/basis of morality. It was hard to live and let live in the face of what felt like busy-body injustice that verged on authoritarianism.

As for The Hunger flyer, I tucked it away and kept it because, hell, it floated down on me from a lamp post while I was at a raucous Meat Puppets/Black Flag show. The flyer stopped me in my tracks: couldn’t wait to run off to the movies to see David Bowie on a big screen. I guess my glam soul still believed in Life on Mars after all.

As for The Hunger flyer, I tucked it away and kept it because, hell, it floated down on me from a lamp post while I was at a raucous Meat Puppets/Black Flag show. The flyer stopped me in my tracks: couldn’t wait to run off to the movies to see David Bowie on a big screen. I guess my glam soul still believed in Life on Mars after all.

(Hence the Pris look I took on for a while.)

Missing are pictures of direct political actions in the Chimes Street Ghetto by folks I admired, like Poo Poo, a petite young woman with a shaved head, self-piercings—seemed she always had a beer in one hand and colorful flyers in the other. Not totally fair, but that’s what memory does: edges blur, details fall away. This brief window of time shaped me, and Poo Poo was an agent of change. I remember the first time I saw Poo Poo hanging out in the crook of a tree, out of the sun, and handing out flyers. She rang the bell about military actions in Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador that were sanctioned by the Reagan administration. A few of my circle of friends went to see Atomic Café, and soon, the flyer collection grew to cover issues of atomic weapons proliferation. Or the plight of endangered species. Or the need to keep alive the increasingly endangered languages of first peoples or even to promote Cajun French, both hot topics then in our neck of the woods. Wish I’d kept more of these ephemera. I learned to use my voice about issues I cared about partly because I was going to college to learn those skills, but also because these friends, these misunderstood and shocking kids, who helped me become someone who was misunderstood and shocking in her own right, at least for a little while—we all just took it for granted that we could say something and be taken seriously, no matter who we were, no matter what we looked like.